Can you think of a narcissist? Some people might picture Donald Trump, perhaps, or Elon Musk, both of whom are often labeled as such on social media. Or maybe India's prime minister, Narendra Modi, who once wore a pinstripe suit with his own name woven in minute gold letters on each stripe over and over again.

But chances are you've encountered a narcissist, and they looked nothing like Trump, Musk or Modi. Up to 6 percent of the U.S. population, mostly men, is estimated to have had narcissistic personality disorder during some period of their lives. And the condition manifests in confoundingly different ways. People with narcissism “may be grandiose or self-loathing, extraverted or socially isolated, captains of industry or unable to maintain steady employment, model citizens or prone to antisocial activities,” according to a review paper on diagnosing the disorder.

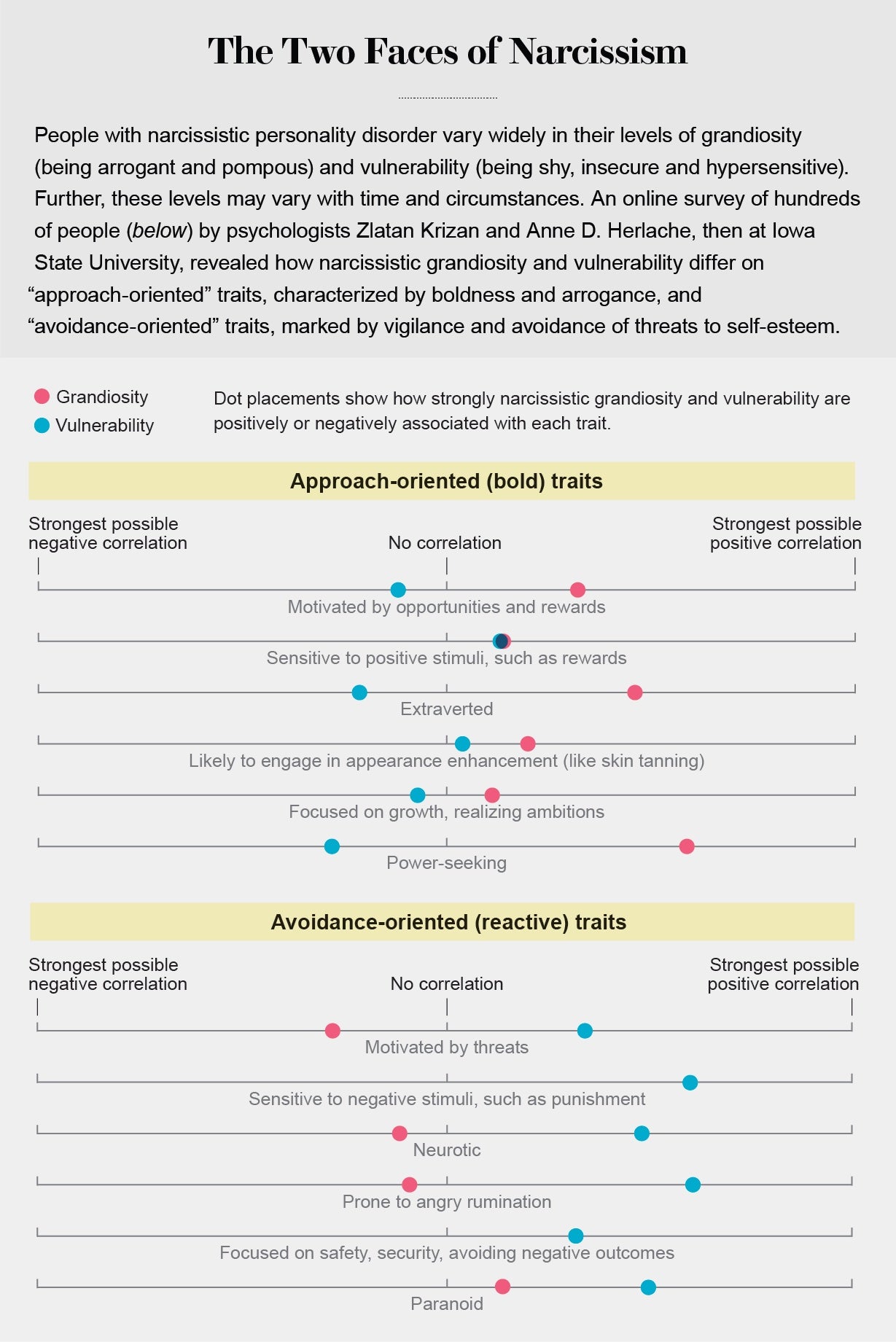

Clinicians note several dimensions on which narcissists vary. They may function extremely well, with successful careers and vibrant social lives, or very poorly. They may (or may not) have other disorders, ranging from depression to sociopathy. And although most people are familiar with the “grandiose” version of narcissism—as displayed by an arrogant and pompous person who craves attention—the disorder also comes in a “vulnerable” or “covert” form, where individuals suffer from internal distress and fluctuations in self-esteem. What these seeming opposites have in common is an extreme preoccupation with themselves.

Most psychologists who treat patients say that grandiosity and vulnerability coexist in the same individual, showing up in different situations. Among academic psychologists, however, many contend that these two traits do not always overlap. This debate has raged for decades without resolution, most likely because of a conundrum: vulnerability is almost always present in a therapist's office, but individuals high in grandiosity are unlikely to show up for treatment. Psychologist Mary Trump deduces, from family history and close observation, that her uncle, Donald Trump, meets the criteria for narcissistic as well as, probably, antisocial personality disorder, at the extreme end of which is sociopathy. But “coming up with an accurate and comprehensive diagnosis would require a full battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that he'll never sit for,” she notes in her book on the former president.

Now brain science is contributing to a better understanding of narcissism. It's unlikely to resolve the debate, but preliminary studies are coming down on the side of the clinicians: vulnerability indeed seems to be the hidden underside of grandiosity.

Fantasy or Reality?

Tessa, a 25-year-old who now lives in California, has sometimes felt on top of the world. “I would wake up every day and go to college believing I was going to be a famous singer and that my life was going to be fantastic,” she recalls. “I thought I could just keep perfecting myself and that someday I would end up as this amazing person surrounded by this amazing life.”

But she also hit severe emotional lows. One came when she realized that the fabulous life she imagined might never come to be. “It was one of the longest periods of depression I've ever gone through,” Tessa tells me. “I became so bitter, and I'm still working through it right now.”

That dissonance between fantasy and reality has spilled into her relationships. When speaking to other people, she often finds herself bored—and in romantic partnerships, especially, she feels disconnected from both her own and her partner's emotions. An ex-boyfriend, after breaking up, told her she'd been oblivious to the hurt she caused him by exploding in rage when he failed to meet her expectations. “I told him, ‘Your suffering felt like a cry in the wind—I didn't know you were feeling that way’ … all I could think about was how betrayed I felt,” she says. It upset her to see him connect with other people; she reacted by degrading his friends and trying to stop him from meeting them. And she hated him admiring other people because it made her question whether he'd continue to see her as admirable.

Not being able to live the idealized versions of herself—which include visions of being surrounded by friends and fans who love and idolize her for her beauty and talent—leaves Tessa profoundly distressed. “Sometimes I simultaneously feel above everything, above life itself, and also like a piece of trash on the side of the road,” she says. “I feel like I'm constantly trying to hide and cover things up. I'm constantly stressed and exhausted. I'm also constantly trying to build an inner self so I don't have to feel that way anymore.” After her parents suggested therapy, Tessa was diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) in 2023.

What makes narcissism particularly complex is that it may not always be dysfunctional. “Being socially dominant, being achievement-striving and focused on improving one's own lot in life by themselves are not all that problematic and tend to be valued by Western cultures,” notes Aidan Wright, a psychologist at the University of Michigan.

Elsa Ronningstam, a clinical psychologist at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts, says the relatively functional variety of narcissism includes having, when things are going well, a positive view of oneself and a drive to preserve one's own well-being, while still being able to maintain close relationships with others and tolerate divergences from an idealized version of oneself. Then there is “pathological” narcissism, characterized by an inability to maintain a steady sense of self-esteem. Those with this condition protect an inflated view of themselves at the expense of others and—when that view is threatened—experience anger, shame, envy and other negative emotions. They can go about living relatively normal lives and act out only in certain situations. Narcissistic personality disorder is a subtype of pathological narcissism in which someone has persistent, long-term issues. It often occurs along with other conditions, such as depression, bipolar disorder, borderline personality or antisocial personality disorder.

The 21st-century Narcissus

In the ancient Greek tale of Narcissus, a young hunter, admired for his unmatched beauty, spurns many who love and pursue him. Among them is Echo, an unfortunate nymph—who, after pulling a trick on one of the gods, has lost her ability to speak except for words already spoken by another. Though initially entranced by a voice that mirrored his own, Narcissus ultimately rejects Echo's embrace.

The god Nemesis then curses Narcissus, causing him to fall in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. Narcissus becomes hopelessly infatuated with his own image, which he believes to be another beautiful being, and becomes distraught when he finds it cannot reciprocate his affection. In some versions of the story, he wastes away before his own likeness, dying of thirst and starvation.

In the 1960s and 1970s psychoanalysts Heinz Kohut and Otto Kernberg sketched what's now known as the “mask model” of narcissism. It postulated that grandiose traits such as arrogance and assertiveness conceal feelings of insecurity and low self-esteem. The 1980 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the main reference used by clinicians in the U.S., reflected this insight by including vulnerable features in its definition of NPD, although it emphasized the grandiose ones. But some psychiatrists contended that the vulnerability criteria overlapped too much with those of other personality disorders. Borderline personality disorder (BPD), in particular, shares with NPD characteristics of vulnerability such as difficulty managing emotions, sensitivity to criticism, and unstable relationships. Subsequent versions of the DSM therefore placed even more weight on grandiose features—such as an exaggerated sense of self-importance, a preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success and power, an excessive need for admiration and a lack of empathy.

In the early 2000s Aaron Pincus, a clinical psychologist at Pennsylvania State University, noticed that this focus on grandiosity did not accurately represent what he was seeing in narcissistic patients. “It was completely ignoring what typically drives patients to come to therapy, which is vulnerability and distress,” Pincus says. “That got me on a mission to get us more calibrated in the science.” In a 2008 review, Pincus and his colleagues discovered enormous variability in how mental health practitioners were conceptualizing NPD, with dozens of labels for the ways in which narcissism expressed itself. But there was also a common thread: descriptions of both grandiose and vulnerable ways in which the disorder showed up.

Since then, researchers have found that both dimensions of narcissism are linked to what psychologists call “antagonism,” which includes selfishness, deceitfulness and callousness. But grandiosity is associated with being assertive and attention seeking, whereas vulnerability tends to involve neuroticism and suffering from anxiety, depression and self-consciousness. Vulnerable narcissism also more often goes along with self-harm (which can include hairpulling, cutting, burning and related behaviors that are also found in people with BPD) and risk of suicide than the grandiose form.

The two manifestations of narcissism are also linked to different kinds of problems in relationships. In grandiose states, people with NPD may be more vindictive and domineering toward others, whereas in vulnerable phases they may be more withdrawn and exploitable.

Self-Esteem Juice

Jacob Skidmore, a 23-year-old with NPD who runs accounts as The Nameless Narcissist on several social media platforms, says he often flips from feeling grandiose to vulnerable, sometimes multiple times a day. If he's getting positive attention from others or achieves his goals, he experiences grandiose “highs” when he feels confident and secure. “It's almost a euphoric feeling,” he says. But when these sources of ego boosts—something he refers to as “self-esteem juice”—dry up, he finds himself slipping into lows when an overwhelming feeling of shame might stop him from even leaving his home. “I'm afraid to go outside because I feel like the world is going to judge me or something, and it's painful,” Skidmore says. “It feels like I'm being stabbed in the chest.”

The desire to fill up on self-esteem has driven many of Skidmore's more grandiose behaviors—whether it was making himself the de facto leader of multiple social groups where he referred to himself as “the Emperor” and punished those who angered him or forging relationships purely for the sake of boosting his self-esteem. Skidmore hasn't always presented himself in grandiose ways: when he was younger, he was much more outwardly sensitive and insecure. “I remember looking in the mirror and thinking about how disgusting I was and how much I hated myself,” he tells me.

Clinicians' evaluations, as well as studies in the wider population, support the idea that narcissists oscillate between these two states. In recent surveys, Wright and his graduate student Elizabeth Edershile asked hundreds of undergraduate students and community members to complete assessments that measured their levels of grandiosity and vulnerability multiple times a day over several days. They found that whereas vulnerability and grandiosity do not generally coexist in the same moment, people who are overall more grandiose also undergo periods of vulnerability—whereas those who are generally more vulnerable don't experience much grandiosity. Some studies suggest that the overlap may depend on the severity of the narcissism: clinical psychologist Emanuel Jauk of the Medical University of Graz in Austria and his colleagues found in surveys that vulnerability may be more likely to appear in highly grandiose individuals.

To Diana Diamond, a clinical psychologist at the City University of New York, such findings suggest that the mask model is too simple. “The picture is much more complex—vulnerability and grandiosity exist in dynamic relation to each other, and they fluctuate according to what the individual is encountering in life, the stage of their own development.”

But Josh Miller, a psychologist at the University of Georgia, and others entirely reject the idea that grandiose individuals are concealing a vulnerable side. Although grandiose people may sometimes feel vulnerable, that vulnerability isn't necessarily linked to insecurities, Miller argues. “I think they feel really angry because what they cherish more than anything is a sense of superiority and status—and when that's called into question, they're going to lash back,” he adds. Psychologist Donald Lynam of Purdue University agrees: “I think people can be jerks for lots of reasons—they could simply think they're better than others or be asserting status or dominance—it's an entirely different motivation, and I think that motivation has been neglected.”

These differences in perspective may arise because different types of psychologists are studying different populations. In a 2017 study, researchers surveyed 23 clinical psychologists and 22 social and/or personality psychologists (who do not work with patients) and found that although both groups viewed grandiosity as an essential aspect of narcissism, clinical psychologists were slightly more likely to view vulnerability as being at its core.

Most narcissists who seek help are generally more vulnerable, Miller notes: “These are wounded people who come in to seek treatment for their wounds.” To him, that means clinics might not be the best place to study narcissism—at least not its grandiose aspect. It's “a little bit like trying to learn about a lion's behavior in a zoo,” he says.

The unwillingness to seek therapy is especially true of “malignant narcissists,” who, in addition to the usual characteristics, exhibit antisocial and psychopathic features such as lying chronically or enjoying inflicting pain or suffering on others.

Marianne (whose name has been changed for privacy) recalls her father, a brilliant scientist whom her own therapist deemed a malignant narcissist after reading the voluminous letters he'd sent over the years. (He never sought therapy.) It was “all about constant punishment,” Marianne says. He implemented stringent rules, such as putting a strict time limit on how long their family of five children could use the bathroom during long road trips. If, by the time he'd filled the tank, everyone hadn't returned to the car, he'd leave. On one occasion, Marianne was abandoned at a gas station when she couldn't make it back on time. “There was [hardly] a day without that kind of drama—one person being isolated, punished, humiliated, being called out,” she remembers. “If you cried, he'd say you're being histrionic. He didn't associate that crying with his actions; he thought it was performative.”

Her father also pitted her siblings and their mother against one another to prevent them from forging close connections—and he constantly looked for flaws in those around him. Marianne recalls dinner parties at home where her father spent hours trying to pinpoint weaknesses among the other husbands and to hurt couples' opinions of each other. When Marianne brought home boyfriends, her father challenged them and tried to prove that he was superior. And despite being a dazzling academic who easily charmed people when they first met, he got fired time and time again because of conflicts at the universities where he worked. “It was all about one-upmanship,” she says. “His impulse to destroy anything that was shiny, that was popular, that was loved—it overwhelmed everything else.”

Malignant narcissists often pose the greatest challenge for therapists—and they may be particularly dangerous in leadership positions, Diamond notes. They can have deficient moral functioning while exerting an enormous amount of influence on followers. “I think this is something that's going on right now, with the rise of authoritarianism worldwide,” she adds.

An Adverse Childhood?

Research with identical and nonidentical twins suggests that narcissism may be at least partially genetically heritable, but other studies indicate that dysfunctional parenting might also play a significant role. Grandiosity may derive from caregivers holding inflated views about their child's superiority, whereas vulnerability may originate in having a caregiver who was cold, neglectful, abusive or invalidating. Complicating matters, some studies find overvaluation also plays a role in vulnerable narcissism, whereas others fail to find a link between parenting and grandiosity. “Children who develop NPD may have felt seen and appreciated when they achieved or behaved in a certain way that satisfied a caregiver's expectations but ignored, dismissed or scolded when they failed to do so,” Ronningstam summarizes in her guide to the disorder.

Skidmore attributes his own NPD to both genes and painful childhood experiences. “I've never met a narcissist who has not had trauma,” he says. “People just use love as this carrot on a stick [that] they hang above your head, and they tell you to behave or they'll take it away. And so I have this mindset of, ‘Well then, screw it! I don't need love. I can take admiration, achievements, my intelligence—you can't take those things away from me.’

Many researchers nonetheless say a lot more work is needed to determine what role, if any, parenting plays. Miller points out that most research to date of grandiosity, in particular, has found small effects. Further, the work was done retrospectively—asking people to recall their past experiences—rather than prospectively to see how early life experiences affect outcomes.

There is another way to study what is going on with a narcissist, however: look inside. In a study published in 2015, researchers at the University of Michigan recruited 43 boys aged 16 or 17 and asked them to fill out the Narcissism Personality Inventory, a questionnaire that primarily measures grandiose traits. The teenagers then played Cyberball, a virtual ball-tossing game, while their brain activity was measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a noninvasive neuroimaging method that enables researchers to observe the brain at work.

Cyberball tests how well people deal with social exclusion. Participants are told that they're playing with two other people, although they are actually playing with a computer. In some rounds, the virtual players include the human participant; in others, the virtual players begin by tossing the ball to everyone but later pass it just between themselves—cutting the participant out of the game.

The teenagers with higher levels of grandiose narcissism turned out to have greater activity in the so-called social pain network than those with lower scores. This network is a collection of brain regions—including parts of the insula and the anterior cingulate cortex—that prior studies had found were associated with distress in the face of social exclusion. Interestingly, the researchers did not find differences in the boys' self-reports of distress. In another revealing fMRI study, Jauk and his Graz colleagues found that men (but not women) with higher levels of grandiose narcissism showed more activity in parts of the anterior cingulate cortex associated with negative emotions and social pain when viewing images of themselves compared with images of close friends or strangers.

The bodies of narcissists bear evidence of elevated stress. Studies indicate that men with more narcissism have higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol than those with less narcissism. In a 2020 study, Royce Lee, a psychiatrist at the University of Chicago, and his colleagues reported that people with NPD—as well as those with BPD—have greater concentrations of molecules associated with oxidative stress (a stress response seen at the cellular level) in their blood.

Such findings suggest that “vulnerability is always there but maybe not always expressed,” Jauk says. “And under particular circumstances, such as in the lab, you can observe signs of vulnerability at a physiological level, even if people say, ‘I don't have vulnerability.’” He adds, however, that these studies are far from the last word on the matter: many of them have a small number of subjects, and some have reported contradicting findings. Follow-up studies, ideally with a larger number of individuals, are needed to validate their results. The neuroscience of narcissism “is incredibly interesting, but at the same time, I'm very hesitant to interpret any of these results,” says Mitja Back, a psychologist at the University of Münster in Germany.

Toward Treatments

To date, there have been no randomized clinical trials for treatments specific for narcissistic personality disorder. Clinicians have, however, begun to adapt psychotherapies that have proved to be effective in other related conditions, such as borderline personality disorder. Treatments currently used include “mentalization,” which aims to help individuals make sense of both their own and others' mental states, and “transference,” which focuses on enhancing a person's ability to self-reflect, take the perspective of others and regulate their emotions. But there is still a dire need for effective treatments.

“People with pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder have a reputation of not changing or dropping off from treatment,” Ronningstam says. “Instead of blaming that on them, the clinicians and researchers need to really further develop strategies that can be adjusted to the individual difference—and at the same time to focus on and promote change.”

Since discovering she has NPD, Tessa has started a YouTube channel called SpiritNarc where she posts videos about her experiences and perspectives on narcissism. “I really want the world to understand [narcissism],” she says. “I'm so sick of the narrative that's going around—people see the outside behavior and say, ‘This means these people are awful.’” What these people don't see, she adds, is the suffering that lies below the surface.