Nonfiction

Nurturing Uncertainty

What can Antarctica's "doomsday glacier" teach us about community?

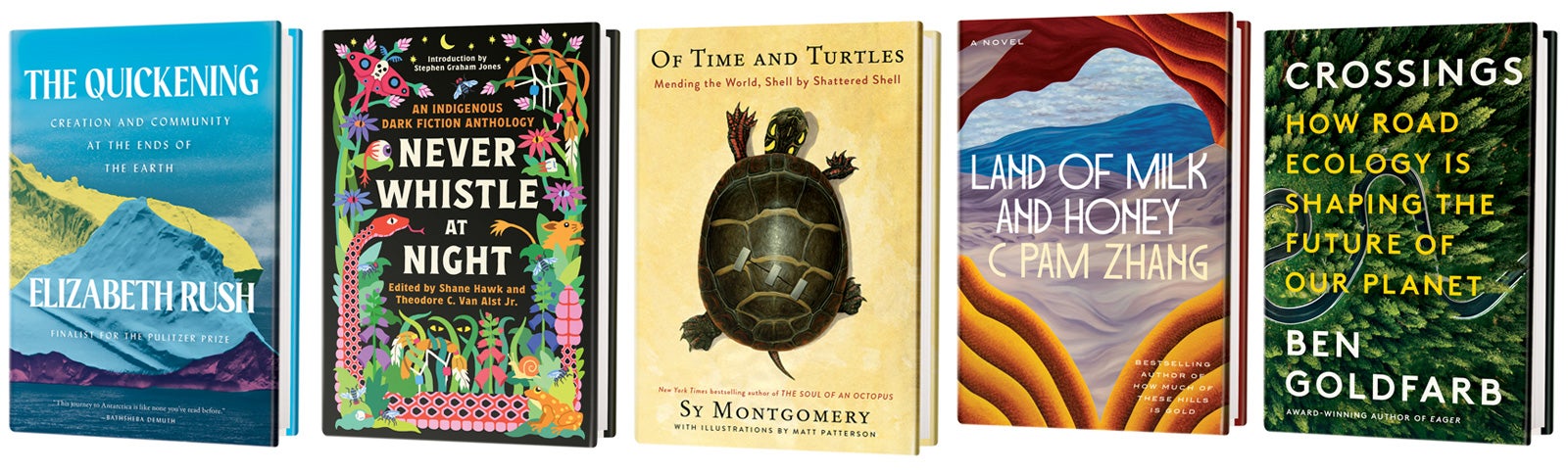

The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth

by Elizabeth Rush

Milkweed, 2023 ($30)

As writer Elizabeth Rush prepares for her two-month expedition to Antarctica, on an icebreaker ship staffed with scientists from around the globe, she is focused on danger and on scarcity. The researchers are traveling to the Thwaites Glacier, a behemoth whose potential collapse could dramatically reshape the time line and scale of sea-level rise. “Will Miami even exist in a hundred years?” Rush muses. “Thwaites will decide.” The glacier juts out into the Amundsen Sea, which is inaccessibly frozen over except for a few weeks in January and February. Rush solicits advice about what to pack for this precious window of data gathering—treats for when the ship's galley runs short of fresh produce; work gear that will fit her female form better than the government-issued versions—and about how to stay safe amid the extreme isolation of the voyage. It seems to be the start of a classic adventure tale.

In some ways, it is. Rush structures the journey as a four-act play, complete with a cast of characters listed before the first chapter. In act 1, the group members prepare for departure, savoring their last chances to have a drink or go for a terrestrial jog. Act 2 brings them to literally uncharted waters, where they take sonar readings to map the ocean floor and test a submarine to see if it can be successfully launched. They take inflatable boats from the relative safety of the giant ship onto a tiny island, where they follow a penguin trail and scour the beaches for penguin bones. Throughout, Rush offers keen observations of the fieldwork and lyrical depictions of the setting, in turn menacing and ethereal. In a moment of great danger, “the bergs are many, lavender and faceted, when the air is full of floating ice crystals.”

But Rush is not at the bottom of the world to conquer, survive, test her mettle, compete or plant a flag. Her journey, woven through the story of the voyage, is a much quieter one: to explore her desire and uncertainty about becoming a parent. Rush is 35 years old when she joins the expedition and worried about the closing window of her fertility. Pregnant people are not allowed on the long and dangerous cruise, and so joining the trip means that she and her husband have delayed trying to start their family by a year. Alongside the dramas on the ship—including treacherous storms and a medical evacuation—she reckons with an interior question that is increasingly familiar: Is it ethical to bring a child into a world so threatened by climate collapse?

As dozens of climate researchers head toward the “doomsday glacier,” this question is thrown into especially sharp relief. Resonances arise organically among the potential futures of Antarctica, the challenges of predicting the climate system, and motherhood. All are uncertain, and all are attached to unforgiving deadlines. “I know what it feels like to fear that there may not be many meaningful strategies left,” Rush writes. In another instance, “there is a clock, and it is ticking.” She could be talking about her own fertility, the window of time in which humanity must move away from fossil fuels or the team's need to gather what data it can before the Amundsen Sea freezes it out.

Rush's preoccupations guide the course of the inquiry, but her view of both the ambivalence of parenthood and the perception of Antarctica is one of many. Her shipmates are co-narrators, with snippets of their interviews peppered throughout her prose. A marine geophysicist, for instance, details the extensive child care arrangements that made it possible for her to do the trip. When everyone gathers on the deck as the first iceberg comes into view, Rush likens the ice to “whipped meringue piped into a lopsided point.” For others, it evokes the geological shapes of Utah, a ski slope or the movie Happy Feet.

By collecting and highlighting a multitude of voices, Rush explicitly works against the classic storylines that dominate Antarctic history: “Amundsen's conquest of the pole, Scott's death eleven miles from One Ton Depot, Shackleton's miraculous return, Douglas Mawson shooting and eating his sled dogs.” Those tales center on the heroics of an individual (who is always a man and almost always white, Rush notes). The Quickening instead offers an exploration story that is also a literature of community, as attentive to the cooks and the marine techs as it is to the scientists whose work they support.

Rush herself pitches in with the data collection—sometimes helpfully and once, memorably, to disastrous effect—and she comes away with a fresh view of the work of scientific research, something she begins to understand as “a deeply communal act.” Ultimately Rush determines that the work of parenting, like the floating village of people studying the glacier, is paving the way for other, better futures.

Rachel Riederer is a writer and editor focusing on climate and culture. She lives in New York City.

Fiction

Revenge of the Land

Powerfully unsettling fiction from Indigenous writers

Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology

Edited by Shane Hawk and Theodore C. Van Alst, Jr.

Vintage, 2023 ($17, paperbound)

Although they are mostly set in the present, the past haunts these unsettling dark fantasies and straight-up horror tales from Indigenous authors. Mining rich strata of poisoned history and blood-soaked land, the writers summon an exhaustive array of ghosts, wolves, Wendigo spirits, human eaters, conjure women, and petroglyphs willing to exact revenge if you scratch them with your car keys. Throughout the 26 stories, contemporary American life is a threadbare bandage soaked through with the gore of the wound it never truly covers or heals.

In Rebecca Roanhorse's standout “White Hills,” an Instagram influencer's #blessed life is threatened by her casual mention of Native American ancestry. Perhaps the collection's most visceral story, it examines eugenics and phrenology-based racism and builds to scenes of brutal horror. Nick Medina's piercing “Quantum” likewise turns on questions of genetics, when the mother of two young children from different fathers learns, after blood testing, that one qualifies as a tribal member, entitled to casino money, while the other doesn't. The true terror in both stories comes from the protagonists' desperation to either claim or hide Indigenous lineage.

In story after story, whether in subdivisions or scrub grass, the protagonists find the past—“the old ways”; “country nonsense”—seeping into their now. In one, the ghost of General Custer's widow physically attacks the narrator with “the strength of death.” Spirits take revenge, old truths suddenly get proven again, and professors—in Mathilda Zeller's “Kushtuka” and in Amber Blaeser-Wardzala's scathing “Collections”—are eager to mount Native American tools (and worse) on their walls, as if their utility has passed.

Ownership of stories, and the way they change in the telling, is a pressing concern. In Darcie Little Badger's “The Scientist's Horror Story,” a geologist regales scientist friends at a convention with his own tale of searching a New Mexico ghost town for whatever has been transforming victims' genomes into “a nonsensical pattern of nucleotides.” (One listener takes notes on holes in the plot.)

After building to a classic ghost-story climax, the speaker somewhat sheepishly agrees that it was all made up, just a spooky laugh, letting his audience off the hook from feeling obliged to think about such things—or, by implication, the blood that seeps through the bandage. —Alan Scherstuhl

In Brief

Of Time and Turtles: Mending The World, Shell by Shattered Shell

by Sy Montgomery. Illustrated by Matt Patterson

Mariner Books, 2023 ($28.99)

The movie portrayals of turtles as ultrachill surfers or pizza-ordering elite fighters have little in common with the richly understated lifestyle Sy Montgomery chronicles during the year she spends volunteering at a local turtle sanctuary. There's abundant drama in the high-stakes field trips: rescuing the victims of hit-and-runs, unearthing freshly laid eggs, releasing rehabilitated “herps” into the wild. But it's Montgomery's heart-tugging conversations with teammates and her commitment to helping an octogenarian named Fire Chief that reveal turtles to be perfect conduits for meditations on aging, disability and chosen family. —Maddie Bender

Land of Milk and Honey: A Novel

by C Pam Zhang

Riverhead Books, 2023 ($28)

When a thick layer of global smog causes crop failure, extinctions and famine, a struggling cook eagerly accepts an offer to work as a private chef for an insular community of elites perched on a mountaintop high above the choked atmosphere. Though ensconced in environmental privilege and culinary abundance, she soon discovers that her new post comes with troubling expectations. As her cryptic employer takes drastic measures to secure the community's future, she must choose whether to remain there or break free. Writer C Pam Zhang's lush but precise descriptions and inventive premise create a thought-provoking fusion of the sensory and the speculative. —Dana Dunham

Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet

by Ben Goldfarb

W.W. Norton, 2023 ($30)

Roads may be connective for humans and commerce, but they're distinctly disruptive to ecosystems and wildlife, writes journalist Ben Goldfarb in this swift and winding ride through the science of road ecology. He covers pumas, passages and pavement with equal parts mirth and earnestness, resulting in a surprising reflection on what we owe to nature. Many readers came away from Goldfarb's first book, Eager, as newly minted beaver fans; don't be surprised if you finish Crossings as an evangelist for road ecology. At the least, the roadkill you spot along the highway will never look the same. —Tess Joosse