In just a few months, NASA will celebrate the 60th anniversary of American astronauts’ venturing into outer space. Alan Shepard’s 15-minute suborbital ride started the journey. Just two and half months later Virgil (Gus) Grissom reached a height of 118 miles, and seven months after that John Glenn circled the Earth three times.

Long before the initial Mercury space flights blasted off, much longer flights were already planned. As the number of Earth orbits in a mission increased, the physiological concerns surrounding keeping humans alive and functioning at peak performance in difficult environments for extended time periods came to the fore.

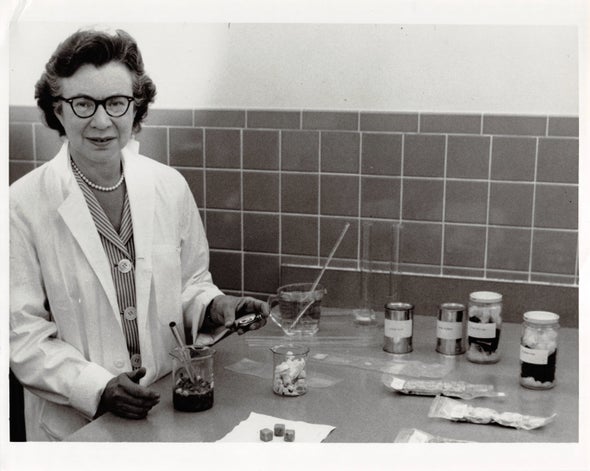

Beatrice Finkelstein, as chief of the Food Technology Section of the Life Support Systems Laboratory at Wright Patterson Air Force Base, bore responsibility for managing the nutritional needs of the astronauts. Her work in the field of space feeding was instrumental in developing the equipment and techniques used in early space flight. Few, if any, female contributors played as important a role as she did during the early years of the U.S. crewed space program, and she deserves to be better remembered and lauded.

Finkelstein’s value to America’s space missions went well beyond her technical contributions. She was frequently described in the popular press at the time as “the Nutritionist to the Astronauts,” as well the proprietor of “Bea’s Diner,” a then widely known semantic construction designed to appeal to the public as a singularly friendly place within the otherwise all-business space program. In Bea’s Diner, high technology and home economics mingled.

In the weeks prior to each manned space mission of the Mercury space program, from 1961 to 1963, Finkelstein traveled from Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, to Cape Canaveral, Fla., in order to oversee the preflight and in-flight feeding of the astronauts. “Bea’s Diner” was situated in the specially designed, purpose-built facility just behind Hangar S, the massive warehouselike facility that was dedicated to astronaut training and served as their crew quarters. This was the place in which all seven astronauts of the initial Mercury Project ate their highly engineered preflight meals.

In her role as nutritionist for the early space program, Finkelstein grew to know the astronauts well, as she interacted with them frequently. At times, she would step beyond her formal role as nutritionist, providing emotional and psychological support to the astronauts. On many occasions, she was one of the last people the astronauts interacted with before launch, and there’s considerable anecdotal evidence that shows her friendship was a source of comfort during the stressful prelaunch activities.

Among the innovations coming out of the Life Support Systems Laboratory in Dayton were “astronaut rations,” the specially processed and packaged foods designed to provide adequate nutrition and eating enjoyment while conforming to the unusual and stressful environment of a space capsule. The Mercury space feeding mission was explained in official Air Force documentation in this way:

“This feeding program is aimed toward providing food with adequate nutrition and a moderate degree of acceptability. Liquids and semisolid foods will be packaged and consumed from collapsible "squeeze" tubes. The tubes will make the use of usual utensils unnecessary. A pontube (a space feeding device consisting of a squeezable polystyrene base and straw) fitted to the end of each tube will be placed directly in the mouth and food will be transmitted by applying pressure to the tube. Solid foods will be in bite-size pieces, each bite individually packaged.”

In addition to the oversight of the space feeding program, Finkelstein played a key public relations role, which she seemed to enjoy. Although few internal documents relating to image-building activities for nonastronauts have been located in archives, it isn’t terribly hard to infer that purposeful effort was expended by the public affairs offices of both NASA and the U.S. Air Force towards promoting the image of Finkelstein as an active and important female technical contributor.

Between 1958 and 1962, hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles were published specifically about Finkelstein. These articles often included her photo and consistently portrayed her as an accomplished expert in the science of nutrition who took that most earthbound of knowledge categories—home economics—and transformed it into the highly technical form required to make sure the dietary needs of humans in space were met, preflight, in-flight, and postflight.

For example, a nearly full-page article in the May 22, 1960, Sunday edition of the Cincinnati Enquirer wrote that, “Men have planned space flight, are engineering the vehicles for it and will be the first to go. But when it came to a question of what they will eat, they left it up to a little woman—Beatrice Finkelstein, chief Food Technology Section, Wright Patterson Air Force Base.” A four-column wide article on Finkelstein in the October 31, 1961, issue of the St. Louis Globe Democrat describes her as a “small, capable woman with a matter-of-fact manner … [who] with others are launching the era of exploration of the last frontier.” The headline of the April 8, 1962, Pittsburgh Press states, “Space Dietitian Shoots for Home Cooked Meal,” and the June 28, 1962, Miami Herald wrote “Petite and full of fun, Bea Finkelstein not only is head coach at the astronaut’s training table, but a close friend of all of them.”

In addition, she appeared on television with some frequency, and this is significant considering that opportunities for airtime in that era were far more limited than they are today. Her most notable appearance occurred on August 25, 1960, when Finkelstein stumped three of the four the panelists on the nationally televised game show What’s My Line?

In this fashion, the public image of nutritionist Beatrice Finkelstein demonstrated that the agencies that insured NASA’s successful space flights were staffed by smart women as well as smart men. But this wasn’t just the concocted effort of a slick public relations campaign. Her role in America’s success in conquering space in the technical field of space feeding served as an example of the role women could and did play in the early space program.